Every shed has a purpose. Across Fogo Island and Newfoundland, small-scale peak-roofed structures are used for storing firewood and fishing nets, for gutting and cleaning fish, repairing boats or amassing junk. Commonplace, vernacular wooden structures, they nonetheless contain within them a modest history of culture and material usage.

With help from three members of the community, Serapinas dismantled an existing shed on Barr’d Islands, Fogo Island, that was destined to be torn down. According to local knowledge, the shed was in fact the third iteration of a similar structure, a slightly different configuration of wooden boards, nails and shingles assembled according to need. Over time, more contemporary additions such as vinyl siding, wallpaper-covered panels and a discarded front door had been integrated with older wooden materials. Thus cobbled together, the shed reflects a natural and economic reuse of materials, a resourcefulness borne of necessity.

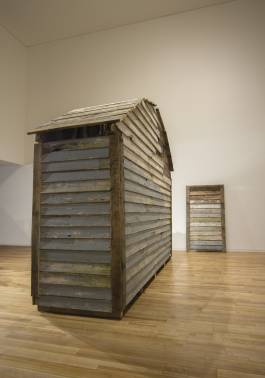

Taken from the original site to the Fogo Island Gallery, the materials of the Barr’d Islands shed are once again reassembled into a new structure that bears its history in peeling paint, handwritten measurements, and notched surfaces.

From a frontal perspective, the new construction resembles a shed, but viewed at an angle it is deceptively shallow. Its shape and size have been determined according to a new purpose and context. The structure’s width ensures it fits through the doors of the gallery, and it is long enough to contain the leftover boards, roof trusses, posts and steps. At the end of the exhibition, the shed’s roof will be removed and stored inside it, transforming the structure into a shipping crate that will travel from Fogo Island to Europe, where it will be dismantled and rebuilt again into other shed-like forms. Like a traveller or immigrant who brings traditions and skills from home and adapts them to a new situation, the shed will take on another life that is dependent on its context.

There is of course an element of the absurd in building and shipping a large crate made from its constituent parts. The initiative calls to mind Jorge Luis Borges’ story of exacting cartographers whose map of their empire matched precisely the scale of the original, a map that would later be seen as irreverent, and then abandoned to the elements.

Yet Serapinas’ work is not a perfect replica of the original. His reconfiguration of the shed is an act of heritage preservation in which he saves a traditional building destined for demolition. This form of preservation does not fix the shed as an artifact, stifling any future development. The shed/crate is in keeping with building and material traditions on Fogo Island that are at once driven by necessity and open to future purposes. In this way, the work employs a form of appropriation and reuse that affirms cultural traditions as ever evolving.

The foreshortened proportions of Four Sheds also speak to the broader problematics of representation, wherein any sign or symbol of a thing is potentially a reduction of the original, and its interpretation is mediated by cultural context and individual perspective. Serapinas’ work is ultimately a modest gesture that speaks of larger things: of place, of shared understandings, of labour and exchange, of material and immaterial things and the structures we build to contain them.